Two years is a long time.

Just two years ago, I’d seen very few Japanese live-action films, only to eventually realise that my interest in anime was linked to a broader fascination with the whole spectrum of Japanese art; what I get from anime, I hear in Japanese music and see in Japanese film, too. This runs deep for me and I can’t explain why, but anyway, since that point, I’ve seen dozens of Japanese films; I have favourite directors and keep finding new music (the latest being World’s End Girlfriend).

Every new film is just the tip of another ice-berg, revealing only further depths of art and beauty. One of my biggest regrets about this blog is that I haven’t documented this journey into live-action nearly well enough, so, I’m sorry about that, guys, but this post, I hope, will at least go some ways to making amends, because last night I watched Air Doll and just had to write something.

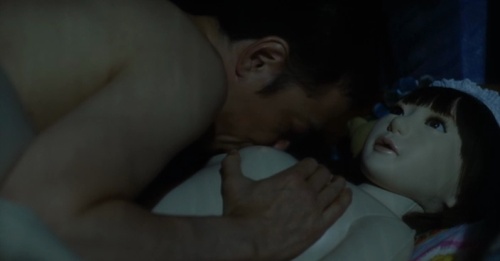

Released in 2009, it’s the (fairy) story of a life-like female sex doll, Nozomi, that, one grey morning, springs into life and stumbles out wide-eyed into the world for the first time.

From the way she walks to her curious interactions with the world, there’s a delightful sense of wonder and naivety to her first steps, offset by the weary people around her. Given its strange subject matter, I think it’s important to note the terminal sadness at the core of the film, but it’s just as important to emphasize the beauty, too. The real, flesh-and-blood people in Air Doll are sad creatures, aching to be loved, yet to see them and the city through Nozomi’s eyes is as poetic as it is tragic.

Barely 10 minutes in, Nozomi’s owner is having sex with her. At this point, she’s still just a lifeless doll, but, for whatever reason, I didn’t find the sex itself as disturbing as seeing the guy (after he’s ‘done’) removing the doll’s plastic vagina and washing it out with soap; the reality of what he’s doing is what’s so terrifying, because, the saddest thing is, people really live like this; he’s walking around his small apartment talking to her about his day as if she were his real, loving wife.

Later on, the owner asks if Nozomi can go back to being just a doll, as if having to deal with a real woman, to consider her feelings, is too much. The point is, people just use Nozomi, the Air Doll, as a substitute for what’s missing from their lives. None of them are willing to consider her feelings. Her love is misplaced and confused, but I shouldn’t dwell on that anymore.

As it draws to a close, Nozomi meets her maker. He asks “Was there something, anything, that was beautiful?” She replies with a nod. The sense of melancholy in this moment is the dichotomy at the heart of Air Doll; that a film as ostensibly grim can feel so warm at the same time is symbolic of just how bitter-sweet and fragile a person’s life is.

Leave a Reply