Earlier this week, Netflix announced that it will begin streaming Neon Genesis Evangelion in April 2019. The 1995 Evangelion TV series is not only one of the most popular anime ever made, it’s also one of the rarest to own on US/UK home video. Since 2005, for various reasons, it has seen neither a home video release nor a legal internet stream, meaning a whole generation of Western anime fans have grown up without (easily) being able to own a copy of the infamous mecha anime.

A change in the anime fan’s mindset

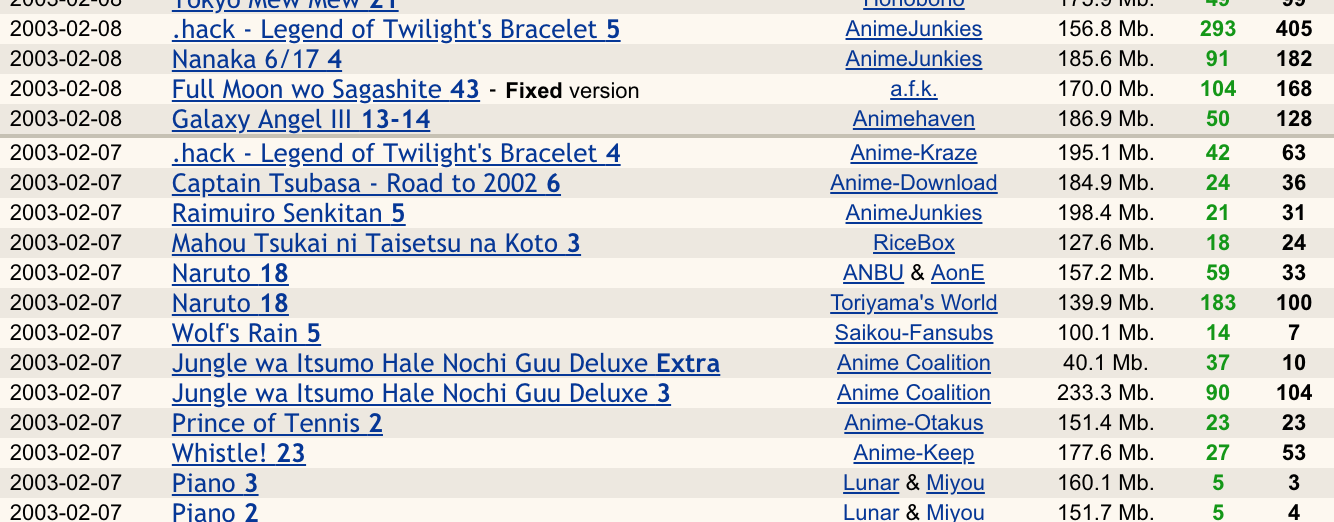

10 years ago, anime fans were experts when it came to sourcing their favourite series. Part of the essential toolkit of being an anime fan included a torrent client, a video player and a codec pack to render the latest episodes. Every week, we waited patiently for our lords and saviours, the fansub groups, to release new anime to us, their devoted masses.

Looking back, it seems ridiculous to me that I ever had to worry about video codecs, but this was the barrier of entry to being an anime fan. Neither finding nor playing the latest anime could be taken for granted.

Everything is different now.

Easier to pay than to pirate

To be an anime fan today, all you need is a subscription to one of Crunchyroll, HIDIVE, Amazon Prime Video or, of course, Netflix. To watch most anime, I just need pick-up my TV remote and press play. Netflix is a particularly popular choice because, content-wise, it has such a broad appeal that whole families share a subscription.

Us anime fans, we used to do things differently. We’d download individual episodes onto our terabyte-sized hard-drives (or, if you were that hardcore, RAID) and maybe burn them onto DVD when you ran out of disk space.

We hoarded anime because it felt like a precious commodity, something that we’d worked hard to find and couldn’t bare to lose.

A few years ago, I binned it all.

Pirating anime was never about getting something for free, I just liked watching new anime. For a long time, there were no legal alternatives to fansubs, other than to wait literal years for a physical release. Some did wait, but most didn’t.

Anime fans were at least a decade ahead of the industry, but the industry slowly caught up to where we are today.

Anime can still fade into obscurity

Who remembers Mōryō no Hako? It was a really promising and weird horror anime from 2008 that I never finished because it took whole years to fansub, nor has it ever seen an official English language translation.

Like many anime before it, Mōryō no Hako fell through the cracks. It’s a good example where the amateur translation community fell flat, but in today’s professional environment, it would have been simulcast with everything else.

Meanwhile, in September, MyAnimeList removed the fansub listings and group reviews from its anime pages in an effort to “support the anime and manga industry”. I doubt we’re losing anything by not knowing who’s ripping Devilman Crybaby, but it’s also a lot harder to track who worked tirelessly to translate Blue Comet SPT Layzner and Panzer World Galient. These types of anime feel harder to discover now than ever, and as we become further entrenched in our streaming platforms of choice, I sense that we’ve become lazier by the day too; many people are now unwilling to look beyond the surface layer of streaming anime. The old ways are disintegrating.

All of this is me trying to understand the sheer noise generated by Netflix licensing Evangelion, as if Evangelion couldn’t be seen until Netflix saved it. Good or bad, it’s just indicative of the way we are as anime fans now: if it’s not streaming, it may as well not exist.

Leave a Reply