The thing is like a wolf.

The thing is a wolf.

Thus, it is a thing to be banished.

I’ve been an anime fan for a long time. At 22, the portion of my life in which I’ve been a fan is already half of that; and the period of time in which I’d been exposed to anime is closer to three-quarters that timespan. As such, good titles often fall by the wayside.Such was the case with Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade. Produced in 1998, it was relatively new when I was first getting regular access to anime. Needless to say, at 11, dubs of Sailor Moon and Pokemon were infinitely more interesting. And so, without ever making it onto so much as a To-watch list, Jin-Roh left my consciousness for the next nine years. And like all good things, it was not only worth the wait, but indeed, a wait I needed. I don’t think I could have appreciated the movie to the extent that I did even five years ago, let alone ten.

Though he had little to do besides write the screenplay, Mamoru Oshii‘s touch is evident throughout Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade. The movie continually threatens to pull the rug out from under your feet, all while providing a structure as organized as latticework. Directed by Oshii’s right-hand man and key animator, Hiroyuki Okiura (after he apparently kicked up a fuss about Oishii‘s handling of some scenes during Ghost in the Shell!) the film begins with a death: a “little red riding hood” delivering bombs to a resistance faction. What follows is a multifaceted account of a country, a man, and an organization. Jin-Roh is a dark film, but one continually punctuated by the light from molotov cocktails. Something’s better than nothing, I suppose.

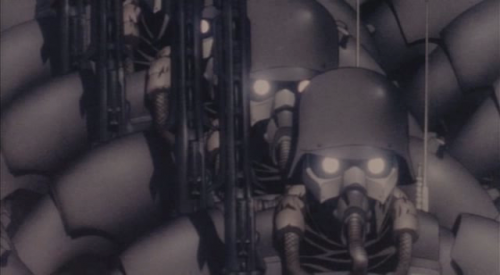

The introduction to Jin-Roh must be one of the most stupefying experiences I’ve ever had. It starts as a factitious account of postwar Japan, and through a constant series of images, some sad violin notes, and steady narration, somehow warps into something different; all of a sudden we’re unsure of where the history ended and the fiction began. Police dressed like Storm Troopers are pictured marching through Tokyo, fighting a rebellious force of young, angry people who come to be known as “The Sect”. The transition from these still photos to animation comes through a series of images: one depicting a man being gunned down, the second depicting the Special Armored Police turning around, slow and alien.

Immediately after this, we cut to a scene of a riot. The noise deafens; in contrast with the silence of the preceding images, the continual yelling of the crowd, the sound of brick and bottles hitting the police’s riot gear is cacophonous. A girl silently walks through the chaos, escapes through the gutters, only to be found by members of Armored Police. Fuse, our protagonist and a member of this unit asks her “why?” to which she shakes her head, silently, and pulls the cord out of the explosive she carries. Fuse spends the rest of the movie contemplating this question, and wondering why he receives no blame, all while repeatedly meeting with a girl that is her exact likeness.

The introduction’s fact-into-fiction transition is mirrored in the copy of Little Red Riding Hood received by the deceased girl’s would-be sister: in this case, the story begins with Little Red Riding Hood scraping her skin raw to escape clothing made of metal, then setting off into the woods, where she is forced to choose between the path of pins or the path of needles. For most, this is an unfamilliar permutation of the tale. The beastly, though elegant Fuse narrates the wolf’s lines near the end, in a ghastly way.

Fuse spends the entire movie in a kind of half-light: he reenters training on the behest of his superiors, meets with but never seems to advance very far with the female lead, Nanami, and on a metaphorical level flickers between being a beast and a human. The scenes involving Fuse almost perfectly flip from day to night abruptly, from light to pitch dark. The “beast” to be banished is the secret unit within the Special Armored Police itself, as other factions within the government seek either to absorb or slander its name. Either way, as a time of peace seems to be settling on the nation, the era of a heavily-armed super-elite police force is drawing quickly to a close.

On the whole, Jin-Roh is presented with a pragmatism and verisimilitude which Oshii seems to have moved away from as his career progressed – the sky-high glittering church scene from Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence comes to mind. In Jin-Roh, There are jurisdictions to be dealt with, and the guerilla warfare the movie deals with is a clear nod towards Vietnam’s political and military strife decades earlier, moreover Japan’s own political situation at the time. It is cinematic in its execution, crystalline in structure, and atmospheric in the extreme, and well worth the watch.

Leave a Reply